Do you have Cherokee Ancestry?

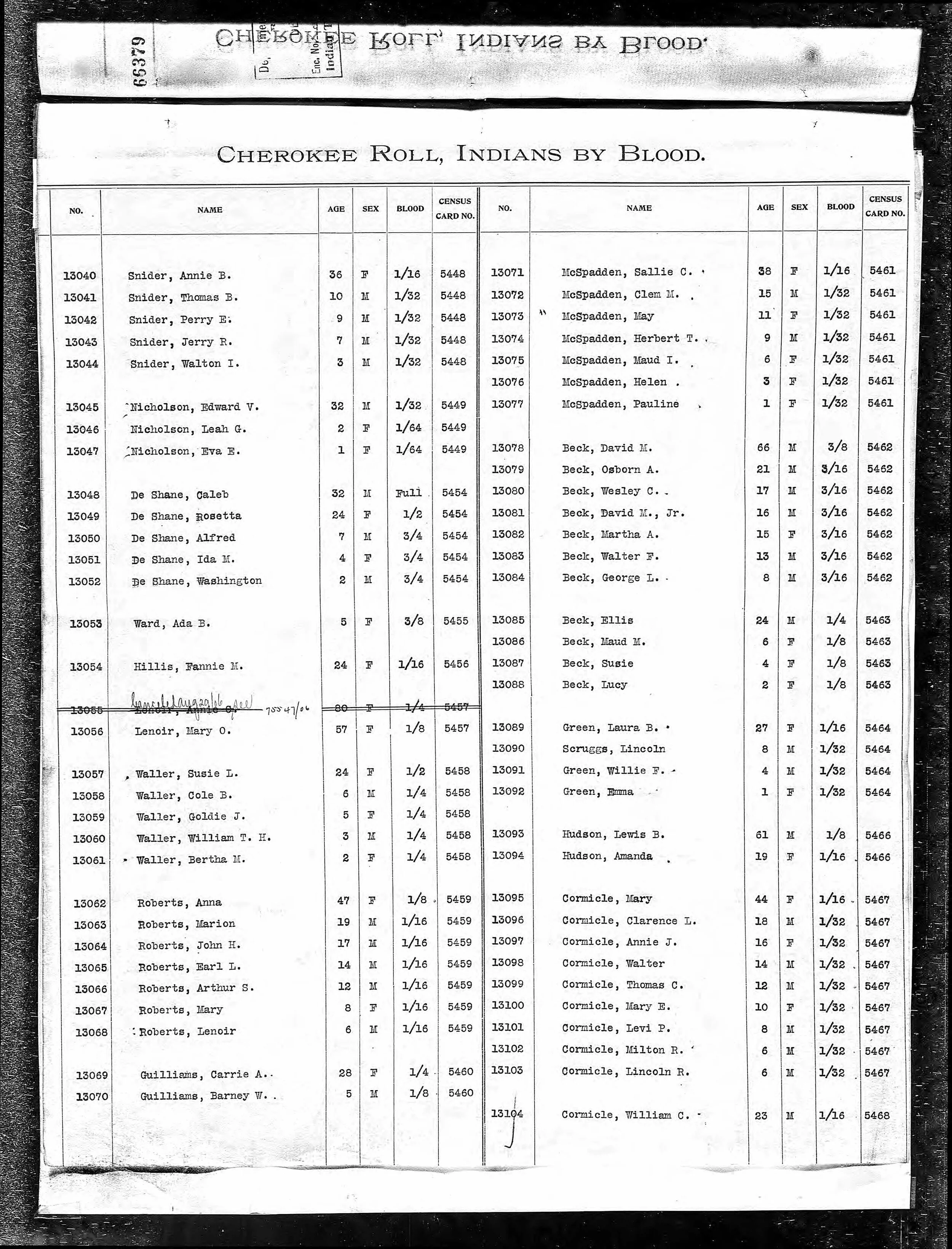

Dawes Rolls Entries

Did you know that a claim to Cherokee ancestry is one of the most commonly-held family history myths among Americans?[1]

I’m not saying YOU don’t have Cherokee ancestry – but I AM saying that many people who believe they possess Cherokee heritage. . . well . . . actually don’t.

This is one reason why, as I recently worked a client project for someone with actual proven Cherokee ancestors, I felt a little like I won the lottery. Upon learning my client’s background, I quickly realized her claim was not your typical “my great-grandmother had high-cheek bones, so that makes us Native American” family myth. Why?

Well, first of all, my client hails from Oklahoma – an area that before 1907 was known as Indian Territory.[2] Her family lived at the right place at the right time to have Native American connections.

Second, she received a card from her mother that states her Cherokee blood percentage. Such cards are issued to individuals who can prove a direct line connection to an individual enumerated on the Dawes Rolls.[3]

A little background:

In 1830 the United States federal government began the process of moving the Cherokee nation from the southeastern United States to land west of the Mississippi River. The presence of indigenous people in the southeast limited the growth of Southern plantations as well as non-native access to valuable natural resources. Beginning in 1838, a poorly executed plan of forced migration to land in present-day Oklahoma led to conditions of disease, starvation and inadequate shelter among the Cherokee. This migration eventually came to be called the “Trail of Tears.”[4]

See* for citation information.

In the years up to and after the Civil War, many non-native settlers moved west beyond the Mississippi River. In Indian Territory, the native nations communally held vast tracks of land previously promised to them for perpetuity by the federal government.[5] Many Americans saw these large swaths of land, much of which was not developed, as wasted farm land. Lawmakers also saw the indigenous peoples’ way of life as antithetical to and incapable of coexisting with the mainstream in regard to property and capitalism. A series of measures were passed seeking to assimilate those of Native American descent into mainstream society.[6]

A commission headed up by Henry L. Dawes began a systematic plan to break-up the land in Eastern Indian Territory previously granted to the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole into individual tracts to be “allotted” to each tribal member, thus introducing private property to the native nations.[7] In order to do so, the plan necessitated taking a roll – commonly referred to as the “Dawes’ Rolls” -- of each legitimate member of the “Five Civilized Tribes.”

I traced my client’s lineage to her direct line ancestors who were indeed enumerated in a Federal Census Indian Schedule as well as in the Dawes Rolls. The Dawes Rolls entries led to me pursue the family’s Dawes Rolls application files. As I buried my nose in the Dawes Rolls applications, I felt for the second time as if I had won the lottery. I am talking multi-page files full of testimony, interviews, and multi-generational family information. Wow!

You can find Dawes Rolls records at both Ancestry and Fold3. I suggest consulting both websites.

So, back to my original question: Do you have Cherokee Heritage? You might. As with any genealogical research question, you start with what you know and work your way back. Perhaps your search will lead to you discover that your family story is more than just a myth!

[1] Gregory D. Smithers “Why Do So Many Americans Think They Have Cherokee Blood? The history of a myth,” 1 October 2015, Slate (Slate.com: accessed 21 September 2020).

[2] Donald E. Green, “Settlement Patterns,” Oklahoma Historical Society (okhistory.org : accessed 13 September 2020) home > publications > Encyclopedia > settlement patterns.

[3] Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Certificate_of_Degree_of_Indian_Blood : accessed 21 September 2020) “Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood” rev. 3 July 2020.

* “Map of the Indian and Oklahoma territories” (Rand McNally and Company); Library of Congress ( https://www.loc.gov/item/98687110/ : 19 September 2020).

[4] Lovelace, “Was Great Grandma Really Native? An Introduction to Native American Genealogy,” 15 April, 2020; webinar online, Legacy Family Tree Webinars. See also, Andrew K. Frank, “Trail of Tears,” Oklahoma Historical Society, encyclopedia online (okhistory.org : accessed 17 September 2020), home > publications > encyclopedia > trail of tears. See also, Steve Inskeep, Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab (New York : Penguin Press), 2015, chapter 21; digital book, Google Books (googlebooks.com : accessed 17 September 2020).

[5] “Description,” Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps, 1893 Map of the Cherokee Strip, (raremaps.com: accessed 17 September), Antique Maps > United States > Plains > Sep. 4 1893 Map of the Cherokee Strip.

[6] Ibid. See also, Wikipedia (Wikipedia.org : accessed 17 September 2020), “Dawes Act.” See also, Alysa Landry, "Paying to Play Indian: The Dawes Rolls and the Legacy of $5 Indians," 21 May 2017, Indian Country Today (Indiancountrytoday.com : accessed 18 September 2020).

[7] Scott, “Description,” Dawes Packets, database online, Fold 3.